The 1916 election sounds oddly familiar

A local historian walks us through the wild gubernatorial election between Thomas Campbell and George Hunt more than 100 years ago

Hank met Arizona-based historian and writer Donna Reiner while they were working the polls together during the primary election. She mentioned this tale about the 1916 election, and we immediately commissioned a piece about it. The story offers a look into the past and a potential vision of the future.

If you like this history lesson, please become a subscriber so we can pay her!

For months following the election, Republicans and Democrats made acrimonious counter-claims of victory.

This may sound familiar to those who followed the 2020 election. And for this writer, the story of Arizona’s 1916 election always comes to mind whenever a candidate starts questioning any election results.

In 1916, Arizona was about to hold its third1 statewide election. Thomas E. Campbell, a Republican, was running against Gov. George Wiley Paul Hunt, the incumbent and a Democrat.

By 1917, Arizona ended up with two governors at the same time — and it took a court intervention and nearly a year to iron it out.

Months of legal fillings led to a protracted delay in settling who actually won the race. In the meantime, the Arizona government was in a suspended state of chaos and dysfunction.

The 1916 Arizona gubernatorial election stands as a warning of how difficult it can be to recount ballots, especially by hand, even based on the less than 60,000 ballots that were considered then.

And it may serve as a preview of what’s to come, if candidates contest the 2022 gubernatorial election results, as Republican Kari Lake has already suggested she will to do if she loses.

Campaigning for that 1916 election in Arizona primarily consisted of speeches and rallies around the state. Of course, there were newspaper ads, but most residents were not subjected to the daily bombardment of political ads that we experience today.

For those who are not that familiar with early Arizona history, the state had entered the Union as a Democratic stronghold. Or so it would seem.

Hunt had already served two terms as governor by 1916. Previously, he had served as the President of the Arizona Constitutional Convention in 1910 and a member of the Arizona Territorial Legislature. Before that, he was the first mayor of Globe.

Looking back, political historians would suggest that there were pre-existing issues that set up that fateful November 1916 election. Perhaps not back-room deals, but definitely issues around labor, business and suggested fiefdoms under Hunt’s previous two terms set the stage for this momentous event in Arizona history.

Hunt had competition during the 1916 Democratic primary for his proposed third term. Since the prevailing newspapers from the time leaned Republican, the stories may be somewhat biased. But it seems that the “Hunt machine” had offended much of the populace, Republican and Democrat, due to overspending, prohibition, deficits, prison policy and other points of contention.

The Hunt and anti-Hunt factions continued to battle before the primary, but the Democratic County Central Committee of Maricopa County ultimately announced its support of Hunt, who easily defeated his primary opponent.

Thus, the stage was set for Election Day, Nov. 7, 1916, between Campbell, a native Arizonan, and Hunt, an early Arizona pioneer. At the same time, President Woodrow Wilson was running for re-election, and America was avoiding becoming involved in the European conflict.

If you think that counting votes and reporting results is slow now using machines, you should have been around in 1916 when the checks and balances of today did not exist. Reporting the results from various precincts took time and then had to be conveyed to the Secretary of State.

Campbell’s camp shared positive news as the votes dribbled in over the next two days, while Hunt’s camp made more dramatic claims of victory.

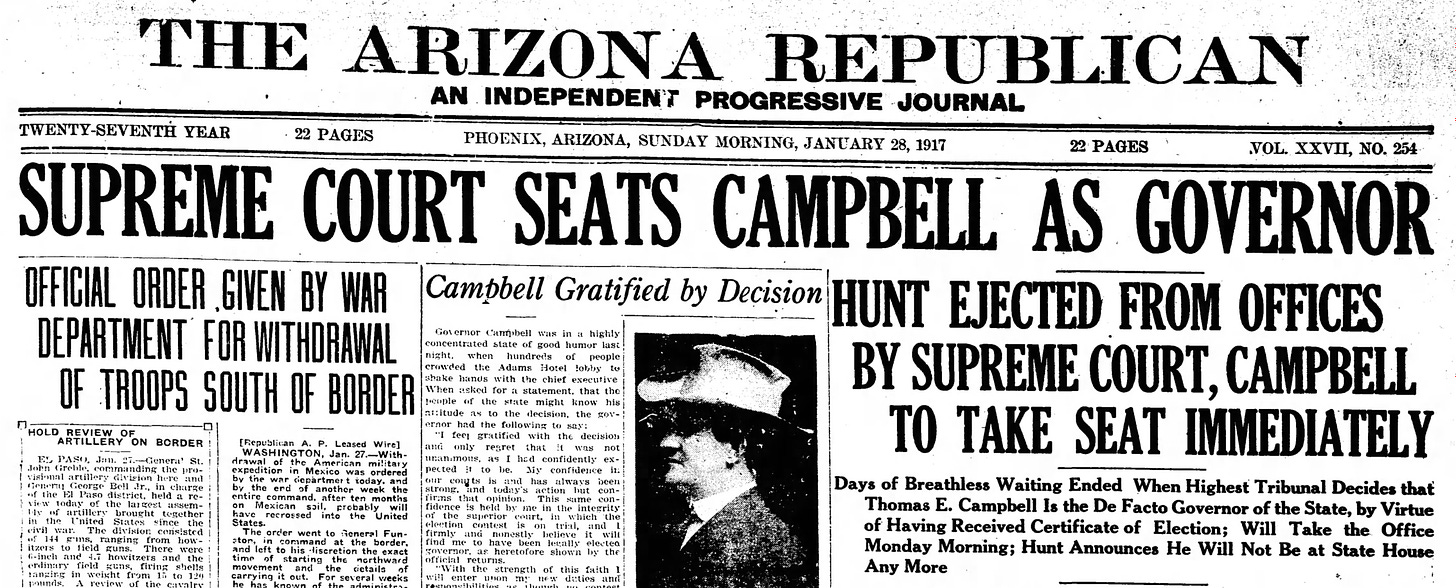

On the morning of Nov. 10, though, the headlines in the Arizona Republican2 read: “On the Face of Returns Mr. Wilson is Re-Elected.” Just below that: “Hunt and Campbell Both Declared Winners by Managers.”

And so it began. Campbell’s lead appeared to be 300 votes, but Hunt’s team claimed Hunt actually had the lead by 146 votes.

By Nov. 12, Campbell’s lead had dwindled to 175 votes as more updates came in from the smaller counties.

Hunt’s people were talking about a recount because of a peculiarity of how ballots were marked and counted. At the time, voters could indicate with a simple cross (+) and vote the entire Republican or Democrat slate. However, in this particular election, many Democrats made that cross AND also placed it in the square by Campbell’s name.

The problem had come up in previous elections, but probably never on this scale. Election officers, by law, rejected these ballots. But counties applied this law inconsistently. The Arizona courts, however, decided that when a voter checked off the box by the party (Republican or Democratic), they meant to vote for all of that party’s candidates, even if the voter had marked one additional candidate from another party.

The argument that they must have meant to vote for me does sound somewhat familiar, doesn’t it?

Grumblings from both parties over the slow pace of the count grew. But at the time, there were only three other states whose populace was as scattered as Arizona’s, which certainly complicated reaching the final results.

Two weeks following the election, only five counties had reported official counts, and four3 were still incomplete. And Campbell’s lead was being slowly chipped away. Apparently, accurately tabulating votes by hand was difficult and time-consuming, even more than 100 years ago.

On Nov. 23, the Arizona Republican announced that Campbell’s lead was only 55 votes. Hunt assured his followers that he would demand a recount. There was even some speculation that Sydney P. Osborn, then the secretary of state, might become the next governor if the vote could not be settled. People were placing bets who would be governor come Jan. 1, 1917.

By the week of Dec. 4, 1916, Hunt’s counsel, Eugene Ives, requested that all ballots be brought to Phoenix to be examined. Ives was rather confident that the examination, especially of Maricopa County votes, would wipe out Campbell’s lead and show Hunt as the winner.

On the afternoon of Dec. 6, Hunt and his attorney appeared before the Maricopa County Superior Court and initiated a recount of the ballots. In the meantime, Campbell’s lead had been narrowed to 30 votes. The recount would look at all the ballots cast and those that were not counted. Naturally, there were concerns that some ballots had already been discarded, but there was no way to verify that or do anything about it.

The recount began Dec. 12, 1916. And yes, minor errors were found on the tally sheets, as the Arizona Republican reported small changes in the overall count. During the recounting, Campbell’s legal team petitioned the court to dismiss the recount on the grounds that Campbell had never been officially recognized as the winner of the election and therefore “his election cannot become a matter of contest.” The judge agreed with Campbell’s attorneys. The legal maze continued with arguments presented by both sides and still no declaration of a gubernatorial winner.

Finally, on the evening of Dec. 20, the counsels of both parties agreed to drop opposition to certifying Campbell as the governor of Arizona.

But for Hunt, his fight to win was not over by any means.

A mere week before Campbell was to take office, Hunt had not even begun to pack up his personal effects. (Again, that sounds familiar, right?) And no one was talking about the move. Hunt’s attorney, Ives, even advised him to stay in his quarters after Christmas because the battle wasn't over.

On Dec. 30, Campbell was sworn in as governor. But Hunt also had himself sworn in as governor and announced he would not quit on Monday.

Two oaths, only one certificate of election. Two messages to the Legislature, with only one person supposedly governing the state. And two men claiming the office, but which one would fill it?

As the Arizona Republican wrote: “Monday will be a regular day.”

Campbell spoke to his supporters from the Capitol grounds on Jan. 1, 1917, instead of from the governor’s office or legislative chambers.

Some claim his outdoor speech was necessary because the building was closed on a legal holiday. But in reality, there were armed lawmen, Hunt supporters, blocking Campbell’s entrance into the executive chambers after he entered the building. Tensions were high, but the day stayed peaceful.

Campbell’s legal team struck the next blow. On Jan. 2, Campbell asked the courts to pronounce him governor and order Hunt to vacate the executive chambers, a request which was eventually heard before the Arizona Supreme Court. Until there was a de facto governor named, the Legislature was not being paid. Campbell conducted Arizona business, although not in the Capitol, while the court silently mulled over the conundrum before it.

Simultaneously, the suit over the ballot count before the Maricopa County Superior Court started up again.

If the citizens of Arizona, the Legislature and county officials were confused about who was governor, imagine the U.S. Postal Service. Letters addressed to the Governor of Arizona were delivered to Secretary of State Osborn.

And then it became clear. At least for a while.

Arizonans awoke Sunday morning, Jan. 28 to the news that the Arizona Supreme Court had declared Campbell the Governor of Arizona, and he would take office on Jan. 29.

While Hunt left the executive suite, he and his legal team saw this as only a minor bump in the road. Hunt’s ego was probably bruised, but he was not ready to quit.

Because the ballot inspection and recount was still underway at the Maricopa County Superior Court, Campbell was only the de facto governor, which meant he would not receive a salary until the election contest was settled.

During that Superior Court proceeding, accusations were made of fraud, corruption and other irregularities, particularly in one Douglas precinct, which led to other small precincts being contested.

Ultimately, this five-month inspection cost over $50,000 and resulted in Campbell being declared the winner by just 67 votes. Hunt’s attorney quickly announced they would appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court.

The case filing in August 1917 was humongous, at over 300 pages. The court began considering the arguments about which votes to accept or reject within the most contested precincts in October and reached its unanimous decision on Dec. 22, 1917, nearly a year after Campbell took office as the de facto governor: Campbell was out and Hunt was declared Governor.

By the Arizona Supreme Court’s final count, Hunt won by 43 votes.

The decision stuck.

Since there was no constitutional question in the hearing, there could be no appeal — only a rehearing. The Arizona Attorney General, a “Hunt man,” demanded that Campbell and his appointees immediately vacate their offices.

As the dust settled and Campbell returned to Phoenix, calm and cordial decisions were made. Campbell wrote a letter to Hunt stating that he would turn over the office to Hunt at 10 a.m. on Christmas Day. All of Campbell’s appointees also submitted their resignations.

The Arizona Republican declared the Hunt-Campbell contest “one of the most remarkable political contests in the history of the country” in an editorial that still holds up today.

Campbell didn’t shy away from running again, though: He successfully won the gubernatorial race in 1918, but not against Hunt. And Hunt did not run again until 1922, when he blocked Campbell from winning a third term.

Donna Reiner, PhD, a local historian, loves to share quirky Arizona history stories. At family gatherings, she often asks if their state can top this latest or rediscovered bit of history especially when it comes to politics.

At the time, state elections occurred every two years.

The Arizona Republican is the original name of the Arizona Republic.

At the time, Arizona only had nine counties.

Another great AZAgenda report. A bit of Norton family history to add. Hunt married one of my thousands of cousins. She and their child are buried with him in the mini-pyramid in Papago Park. Being the descendant of a byzantine horde of Mormon pioneer polygamists means that I get to claim [or have to admit] "cousin" status with a remarkable chunk of the Western States' population.

Our family historians tag Hunt with a bit of a notorious history before first moving to Arizona post Civil-War. (Escaping his home town while he could, as some put it.) Born to a family of slavers? Post Civil War atrocities? A previous wife divorced or abandoned? Life in the wild and lawless mountains of what's now Eastern Arizona and Western New Mexico?

I think that the part that's safe to conclude is that surviving the Civil War was almost as hard as surviving the post-Civil War era. If you want to read some of that history, familysearch.org is a treasure trove of historical news reports, journals, photos and diaries.

What great historical reporting. Thanks!