Can they do that?

On the internet, nobody knows you’re not a lawyer … Felicidades y lo sentimos … And why the funny capitalization?

Lawmakers are considering a plan to embed protection for Arizona school vouchers into the state constitution by strapping it to a renewal of Prop 123, which provides about $300 million per year in additional money for schools from the state land trust.

We wrote all about it in last week’s edition of the Education Agenda. (Subscribe!) The issue has blown up since then.

But one big question we didn’t address is: Can they do that?

We don’t mean politically. We mean legally.

As public education advocates rightly point out, the Arizona Constitution contains a “separate amendment” clause1 that requires any proposed constitutional changes must show up as separate questions on the ballot.

“If more than one proposed (constitutional) amendment shall be submitted at any election, such proposed amendments shall be submitted in such manner that the electors may vote for or against such proposed amendments separately,” the Arizona Constitution reads.

In the last week, we’ve heard from public education boosters who say any attempt to tie vouchers to public school funding is clearly a violation of the separate amendment clause.

And we’ve heard from supporters of the state’s universal voucher program who say the plan definitely doesn’t violate the separate amendment clause.

But lawmakers still haven’t released the text of the amendment that they plan to adopt.

Without that, it’s all guesswork.

And whether the specific amendment that they write does or doesn’t violate that section of the Constitution is above our pay grade anyway — it’s a question for the justices on the Arizona Supreme Court. And we imagine they’ll have to answer it eventually.

But for today, we want to break down what the provision means, how it’s been interpreted over the years and what implications this has for the Prop 123/voucher battle — so that you, dear reader, can be the know-it-all at your next political/education themed dinner party.

Arizona’s founding fathers included the separate amendment clause in the original draft of the state Constitution in order to prevent “logrolling.”

Logrolling is essentially the art of including a popular provision in a bill that is otherwise unpopular. That forces voters to choose between holding their noses and voting for the parts they don’t like in order to get the parts they do like, or voting against something they like in order to stop something they don’t like.

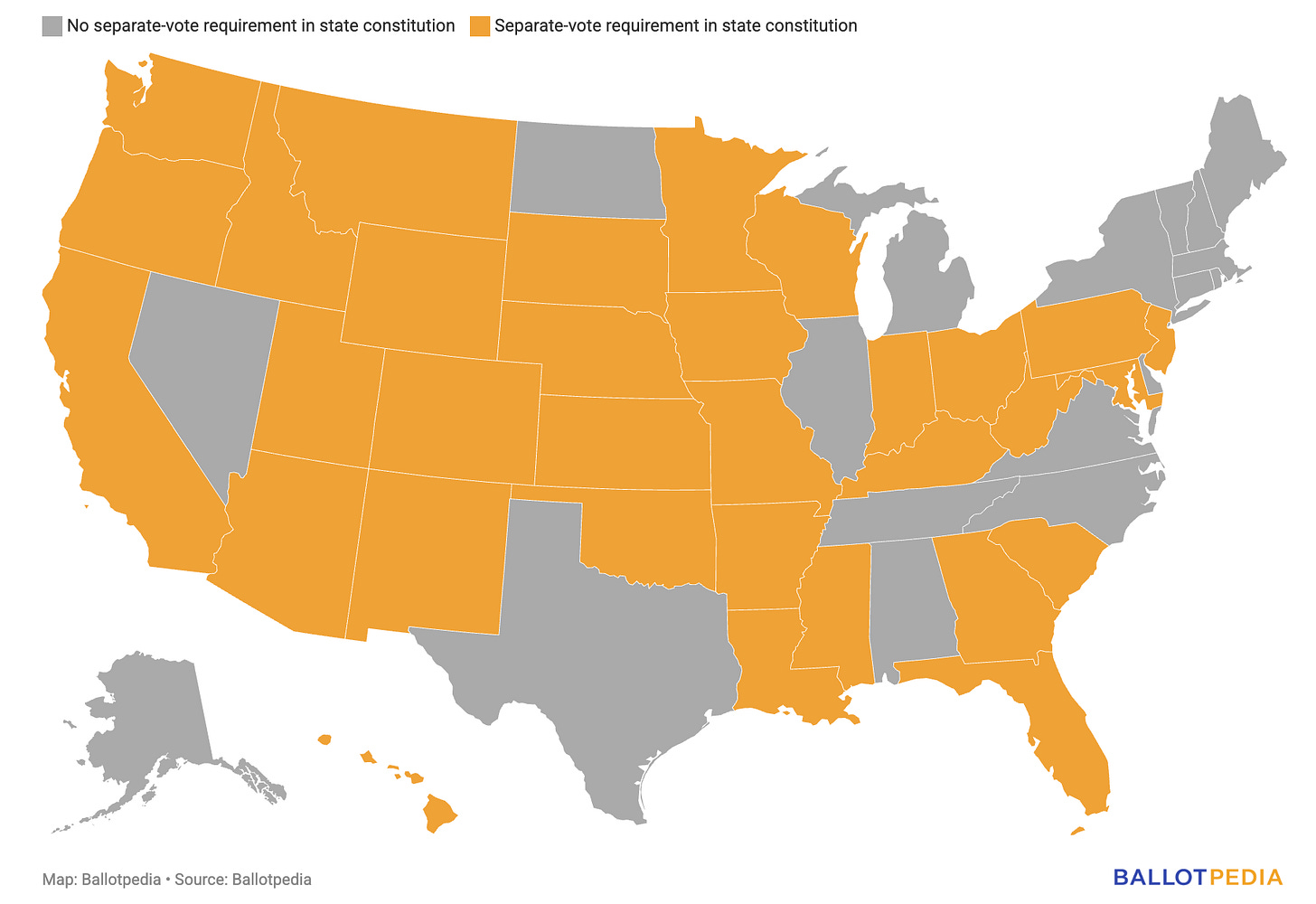

Most state constitutions have some version of the separate amendment provision.

But each state approaches it differently based on the exact language of its separate amendment clause and how it has been interpreted by the courts.

So how do you know if something is one amendment or multiple amendments?

It seems like a pretty straightforward question hinging on the definition of “one.”

But it’s never that simple.

Is it one amendment if it’s all one sentence? How about if the amendment only touches one specific section of the Constitution? What if it’s multiple provisions all on the same topic?

The courts have essentially established that whether “one” means “one” is dependent on all of that and more.

The underpinning of our legal understanding of what constitutes a separate amendment comes from a 1934 case called Kerby v. Luhrs. The case was, somewhat predictably for the time, about taxes on copper mines.

But even the justice opining in that case, Alfred C. Lockwood, acknowledged that the definition of “one” can be more confusing than it sounds.

“There is and can be no disagreement as to the evil the constitutional provision was intended to prevent, and many states, recognizing that evil, have adopted provisions in their Constitution like ours in order to prevent it,” he wrote, referencing logrolling as the evil practice.

“The difficult question, however, is to determine what test shall be used to ascertain whether there are in reality several amendments submitted under the guise of one.”

Lockwood turned to other states that had wrangled with the problem and found a pretty consistent principle, if not a consistent application of that principle.

He tried to restate the collective wisdom as simply as judges in his day could.

Single Amendment:

“If the different changes contained in the proposed amendment all cover matters necessary to be dealt with in some manner, in order that the Constitution, as amended, shall constitute a consistent and workable whole on the general topic embraced in that part which is amended, and if, logically speaking, they should stand or fall as a whole, then there is but one amendment submitted.”

Multiple Amendments:

“But, if any one of the propositions, although not directly contradicting the others, does not refer to such matters, or if it is not such that the voter supporting it would reasonably be expected to support the principle of the others, then there are in reality two or more amendments to be submitted, and the proposed amendment falls within the constitutional prohibition.”

Notice that bolded part there. Lockwood is saying that two ideas that a reasonable voter would find in conflict — like, say, public dollars for private schools versus more money for public schools — cannot be a single amendment.

Under that interpretation, it’s probably safe to say most reasonable voters would find a combination of private school voucher protections and public school funding to be competing — meaning they would support one or the other, but not both.

So slam dunk, right?

Nope.

Fast forward almost 75 years.

In 2006, the Arizona Supreme Court again returned to the question of what constitutes a separate amendment.2

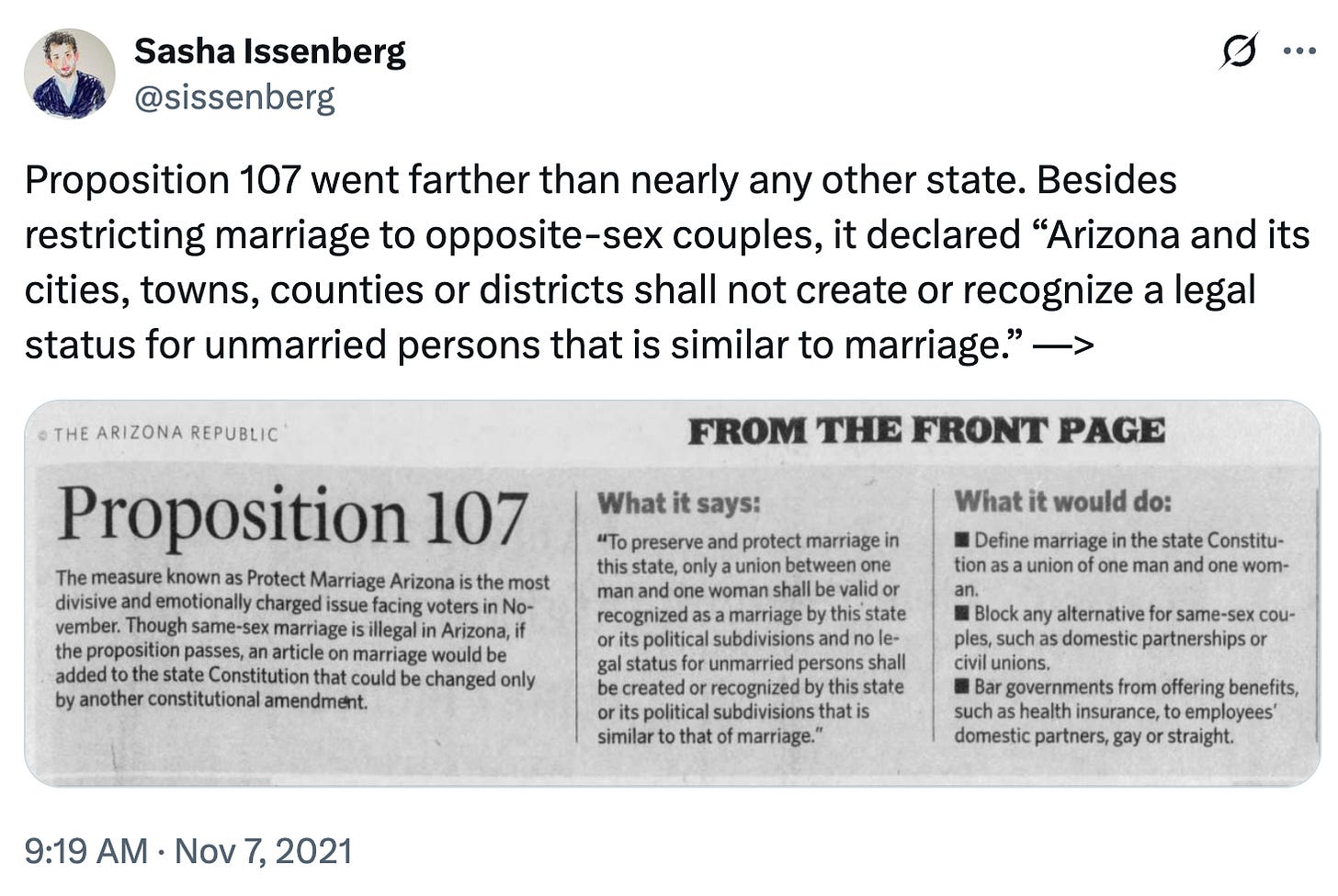

This time, it was about gay marriage in a case called Arizona Together v. Brewer.

Anti-gay groups had proposed a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage called Prop 107. LGBTQ+ groups argued that it was actually three amendments: To ban gay marriage, prohibit civil unions and prohibit the government from awarding benefits and rights to domestic partners.

And they argued, based on polling at the time, that a “reasonable voter” wouldn’t support all three — they may have been in favor of banning gay marriage, but not for barring civil unions and rights for domestic partners.

The court not only rejected that argument, it struck down the whole “reasonable voter” doctrine, saying judges shouldn’t have to speculate about what voters want and there are better ways to determine whether one amendment is actually many.

“(L)itigants have persistently attacked proposed amendments under the reasonable voter approach by using a variety of arguments, most of which asked the Court to speculate about the behavior of the electorate at some future time,” the justices wrote in their decision.

Instead, the court went back to a “topicality and interrelatedness” test. Essentially, do they touch on the same topic? And is one provision logically and reasonably related to the other, even if the two provisions are not actually dependent on one another.

In essence, the court stopped asking the question: “Would a reasonable voter view this as logrolling?”

The Arizona Supreme Court allowed that 2006 constitutional ban on gay marriage (and civil unions and rights for domestic partners) to go to the ballot.

Former U.S. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema chaired the campaign against it, and she writes about the episode in her book, “Unite and Conquer.” The key to their success, she writes, was not focusing on the gay marriage ban, but on the implications for straight people and domestic partners.

“Our campaign message was unique (as was most of the campaign, really). We focused on the impact that the initiative would have on unmarried couples in the state, rather than fighting with the proponents about the merits of same-sex marriage,” she wrote.

Voters ultimately rejected the constitutional amendment, which was kind of an amazing moment, considering gay marriage bans were still pretty popular back then.

What Sinema doesn’t talk about in her book is that, two years later, anti-LGBTQ+ forces at the Capitol went back to the ballot with a more narrowly tailored gay marriage ban that didn’t include civil unions or domestic partnerships.

And voters approved it.3

So what’s the modern-day lesson we should take away from that tale?

Well, while the court stopped questioning whether a regular voter would view a multi-provision constitutional amendment as logrolling, regular voters didn’t.

The exception: Erika Mateo, a Guatemalan woman who gave birth in Tucson while in Border Patrol custody, walked for two days in the desert while eight months pregnant when Border Patrol found her and took her to a detention center last week, she told the Republic’s Raphael Romero Ruiz. Mateo suffered severe dehydration and gave birth at the Tucson Medical Center the day after she was apprehended, and she’s now one of the few asylum seekers to not face an expedited deportation under the Trump administration after local community advocates helped her get pro bono representation. Mateo was released without a bond payment and has an immigration hearing in Tennessee. Her baby, Emily, is a U.S. citizen.

"I believe that the public support for her and the outcry for what was happening might have helped in this case,” Luis Campos, the attorney for Mateo, said.

Deserted by D.C.: Trump’s tariffs and federal downsizing policies are hitting Arizona hard. Arizona PBS is at risk of losing 15% of its budget amid Trump’s executive order ending federal funding for NPR and PBS, while the Arizona Humanities nonprofit stopped issuing grants for things like children’s literacy programs after it lost $1 million in funding, per the Republic’s Stephanie Murray. Meanwhile, funding that was already promised to Arizona arts groups was yanked after Trump canceled several National Endowment for the Arts grants, KJZZ’s Jill Ryan reports.

A slow crawl: Arizona has recouped about 5% of the money it says it lost to a massive Medicaid scheme that targeted Native Americans seeking addiction treatment, Jasmine Demers reports for the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting. The state Medicaid system lost an estimated $2.5 billion paying the fraudulent providers, but recouping those losses is a “highly complex and manual process” that involves repaying the feds for the lost money.

Big Taser money: Axon executives are pouring money into a new organization called Arizonans for a Better Future ahead of a likely legal battle against a new state law that will let the Taser maker build its Scottsdale headquarters without voter approval, the Scottsdale Progress’ Tom Scanlon reports. The Scottsdale City Council is considering hiring outside legal services for $200,000 to fight the new measure that Gov. Katie Hobbs already signed into law, while former Scottsdale Councilman Bob Littlefield is laying the groundwork for a state referendum.

We don’t have Big Taser’s backing, but the backing of our paid subscribers is all we need.

A fox in the henhouse: Hobbs vetoed a bill lawmakers passed with her in mind, the Republic’s Stacey Barchenger reports. Republican Sen. TJ Shope introduced SB1612 to make those seeking state contracts reveal their political donations in response to a group home operator that got a pay increase after donating to political campaigns benefiting Hobbs. The governor didn’t mention that part of the bill in her veto letter and only cited her opposition to a provision that would change procurement law in the state's Medicaid program. Shope called the veto an "alarming example of the fox guarding the henhouse.”

Preston’s Law: Lawmakers passed and sent to Hobbs’ desk a bill that harshens the penalties for multiple people assaulting a single person. It’s called Preston’s Law in honor of Preston Lord, who died after he was beaten by suspected “Gilbert Goons” while leaving a Halloween party in 2023.

DOGE Days of Summer: The progressive group More Perfect Union is putting up billboards trolling Elon Musk for leading mass federal cuts that have hit the country’s national parks, including Saguaro National Park, which has scaled back its hours to save costs, Phoenix New Times’ Morgan Fischer reports. The six billboards across Phoenix and Tucson read “Greetings from Saguaro National Park,” with an asterisk clarifying “Reduced visiting hours made possible by D.O.G.E.”

Congress is considering a bill that would open all sorts of doors for university students in Arizona who want to work with artificial intelligence, and for the tech startups that state officials love to court.

The groundwork has already been laid. Congress just needs to sign on the dotted line.

Subscribe to the A.I. Agenda today so you can see what the deal is!

Gov. Katie Hobbs isn’t being shy about her beef with Republican Sen. Jake Hoffman.

Hobbs has called Hoffman an "indicted fake elector" with a "political agenda and conspiracy theories.”

But now she’s also sneakily trolling him through her vetoes of his bills.

We mentioned one obvious troll via veto the other day, but the Education Agenda caught another pair of sassy vetoes.

Hoffman leads the Senate Committee on Director Nominations, which Hobbs recently withdrew her nominees from due to the pointed, political, and sometimes personal questioning they faced.

It’s often referred to by its acronym — as the DINO committee.

“This bill is Detrimental, Ineffective, Nonsensical, and Objectionable,” Hobbs wrote in a pair of vetoes of Hoffman’s bills.

Yes, the capitalization is hers.

The separate amendment clause is a lot like the “single subject” rule in the Arizona Constitution, except that it only applies to constitutional changes and it has been interpreted by the courts more strictly than the single subject rule.

Yes, there were lots of cases in between. For simplicity's sake, we’re not getting into those. This email is long enough already.

That provision in the state Constitution was eventually invalidated by the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges. Though it’s technically still in our Constitution.

Great article today!

Shoving vouchers into the Prop 123 renewal is a textbook example of logrolling, exactly what Arizona's founders were trying to prevent with the separate amendment clause.