Arizona’s weirdest bromance

Adrian Fontes and Stephen Richer were political enemies. Now they’re more like frenemies.

I was a young, underemployed reporter in 2009, hanging around the now-defunct Conspire Cafe, a hub for radicals and the home of the anarchist library, talking with a barista who was a godfather of the local anarchist scene.

A big, chatty, baritone-voiced fellow in a suit sat across from me on a barstool. He stood out like… well, a guy wearing a suit in an anarchist library and cafe. I was immediately suspicious of him.

But he was clearly a regular, friends with the anarchist barista. Eventually, we started talking about how I’d recently interviewed Amy Goodman, host of the far-left independent news radio show Democracy Now. The suit said he was a lawyer and a big fan of Goodman’s. After talking for a while, he invited me to join the local chapter of the Freemasons, where I gathered he was some kind of bigshot.

Not a chance, narc, I thought to myself. But I took his card anyway.

That’s how I met Adrian Fontes.

Fast forward to the spring of 2019.

Fontes is two years into his term as Maricopa County Recorder. I’m standing in the parking lot of his office surrounded by a group of election deniers who were determined to prove that Democrats — and Fontes in particular — had rigged the 2018 election for U.S. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (back when she was still a Democrat) and then-Secretary of State Katie Hobbs.

They’re all crowding around a lanky, smiling red-headed guy in a wrinkled dress shirt who’s explaining how to use the terminals inside to look up voter information. He’s the lawyer doing an “audit” of the 2018 election in Maricopa County for the AZGOP1, but the rumor mill already knows he’s also gearing up for a run against Fontes in 2020. As he speaks, the crowd gets increasingly agitated, ramping up their rhetoric and conspiracy theories about how Democrats cheated.

I’ll never forget watching the expression on his face turn as it dawned on him that the volunteers were, in fact, a little too nutty. At some point, the lawyer simply walked away, leaving me with the crowd of election deniers in the parking lot.

That was my introduction to Stephen Richer.

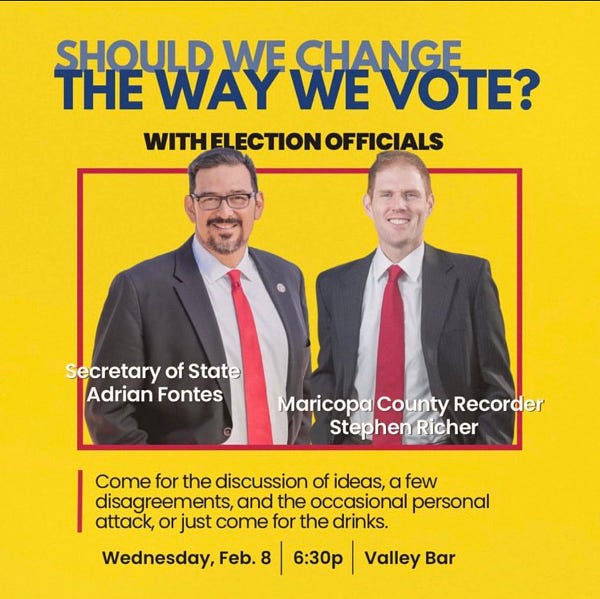

Those two scenes were playing in my head Wednesday night as the political rivals took the stage at Valley Bar in downtown Phoenix — where the two now-nationally-recognizable “defenders of democracy” each have a cocktail named in their honor — offering backhanded compliments and talking about how their “bromance” has blossomed in recent years through the shared trauma of running elections in Arizona.

They say politics makes strange bedfellows. But Fontes, Arizona’s Democratic secretary of state, and Richer, Maricopa County’s Republican recorder, may be the strangest bedfellows of all.

“There was a point in time where I held Stephen in the deepest, deepest disdain. And I genuinely wished him great ill. And he deserved it, you know?” Fontes said from the stage at the standing-room-only event.

That disdain dates back to the audit Richer did of Fontes’ performance in handling his first election in 2018. And to the 2020 election, when Richer ran against an incumbent Fontes for county recorder and beat him, a loss that clearly still stings for Fontes.

It was a bruising race in which Richer painted Fontes as an inept, if not outright corrupt, official who disregarded the law in an attempt to give his team an advantage. Pro-Richer forces dug up decades-old arrest records from Fontes’ college days when he once led Arizona State University police on a low-speed chase on his scooter. Richer constantly hammered Fontes not only for his actions, but for his style, calling him a "pugnacious street activist," a "buffoon" and generally "just terrible."

In his audit — which was unrelated to the Arizona Senate’s audit of the 2020 election in Maricopa County — Richer thoroughly detailed what he saw as Fontes’ many, many missteps in the job. But the document doesn’t use words like fraud or rigged or any of the other catchphrases that are now part of the right’s standard vernacular on elections. In fact, while it declared some claims against Fontes unsubstantiated, rather than disproven, and took issue with many of his decisions, Richer’s audit largely cleared Fontes of wrongdoing. Even against an upcoming political opponent, there were some lines Richer wasn’t willing to cross in order to win.

Richer defeated Fontes by running on a pledge to “make the Recorder’s Office boring again.” He once declared that unlike Fontes, he would "stay away from controversy."

On that front, Richer has failed miserably. Following his razor-thin victory over Fontes in 2020, many Republicans hoped Richer would be the guy who could figure out how Fontes rigged the election in favor of President Joe Biden.

His response essentially boiled down to, “If Fontes rigged the election for Joe Biden, why didn’t he rig his own election against me?”

Because of that kind of logic, those same GOP election fraud activists who stood alongside Richer in Fontes’ parking lot back in 2019 now hate Richer just as much, if not more, than they hate Fontes. At Valley Bar, the dozen or so election integrity activists in the crowd heckled both elected officials on the stage pretty much equally.

But that fire from the far-right fringe has brought the two men closer than they ever would have imagined.

They’re not friends by any stretch. Their relationship seems like part respectful working relationship, part arch nemesis situation, but the kind where the two would occasionally sit down and talk about their plans over a game of chess, like in comic books or superhero movies.

It’s hard to imagine the former Cato Institute employee and the former regular at Phoenix’s anarchist library agreeing on much, though their biographies and ideologies share some similarities, as all arch nemeses must.

For one, they’re both lawyers: Fontes worked as a prosecutor before going into criminal defense as a solo operator, while Richer worked at a big law firm doing commercial litigation and arbitration. They’re also both former business owners: Fontes owned a downtown grocery store called Bodega 420 (presumably a reference to the shop’s address, 420 E. Roosevelt Street, though you could often catch whiffs of weed during jam sessions on the porch), while Richer has owned a string of businesses, including a video-game-themed restaurant in D.C. and a frozen yogurt shop.

But they come at election administration from two very different worldviews, illustrated by hundreds of small disagreements, including their positions on adjudicating ballots, the process of having humans determine a voters’ intent when tabulation machines cannot because of an errant mark or some other anomaly, like voters filling out their bubbles wrong.

At Valley Bar, Richer argued that Arizona shouldn’t adjudicate ballots at all. Fontes thought that was a terrible idea.

“The warm and fuzzy Democrat thinks we should pay attention to what the voters actually feel,” Fontes said.

“And the Republican wants you to fill out your bubble. Just fill it out!” Richer shot back.

Their bond is formed around knowing the struggle and nuance of administering elections in the largest battleground county in the U.S. — and the blowback and vitriol that comes when you screw up.

Just as Fontes’ tenure as recorder was riddled with controversy, Richer’s first general election was, admittedly, not great.

And perhaps it’s sympathy for what can go wrong — and the intense blowback that comes with screwing up in such a high-profile position — that has allowed Fontes to warm up to the guy who defeated him and who he once wished “great ill” upon. By the same token, perhaps Richers’ struggles in administering the 2022 election have given him more appreciation for the nuanced difficulties of the job and how quickly it can all go off the rails, even if it’s not the recorder’s fault.

It’s a frenemy-ship forged by fire. But it’s still not a friendship.

As Fontes put it while sitting on stage alongside his successor, “The bromance only goes so far.”

Correction: A previous version of this article said the report was at the direction of AZGOP Chair Kelli Ward. It was drafted under the previous chair, Jonathan Lines.

Thanks for another great read, you captured them so well. Both gentlemen have graciously shared their time and expertise with our students. Different perspectives and styles but both clearly dedicated to doing right by voters.

Best journalism in Arizona. Great history