A day inside an Arizona abortion clinic

Abortion is still legal in Arizona for now, and Desert Star Family Planning is still providing the procedure.

The confusing, overlapping laws created by Arizona Republicans to restrict abortion sent providers and patients into fits and starts of abortion access in the past two months while the courts figure out the procedure’s fate.

Since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned nearly 50 years of legal precedence upholding the right to an abortion, some of the state’s providers largely suspended services. Arizona patients have struggled to find abortion care since the ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization.

Unlike other states, Arizona has no explicit trigger ban to automatically outlaw abortions if Roe v. Wade was overturned. Instead, a host of other anti-abortion laws on the books have caused mass confusion about the legality of abortions, both for those seeking services and those providing them.

Abortion is still legal in Arizona.

But ongoing court cases and fear of prosecution have kept some providers from offering abortions. The largest provider in the state, Planned Parenthood, has stopped offering any kind of abortion services.

A few independent providers, like Desert Star Family Planning, have kept at it, adapting to a quickly changing legal landscape to do as many abortions as possible while they’re still legal.

Those providers initially suspended their services after the Dobbs ruling, then resumed abortions after a judge halted yet another anti-abortion law, a so-called “fetal personhood” law that some feared could lead to legal claims on behalf of an aborted fetus. After that ruling, Desert Star resumed abortions.

“I am not concerned with my legal risk at all because I've made it very clear that I don't have the complexion to provide illegal abortions. … I'm a Black woman. You think I would put myself at risk of going to jail? Why would I put you at risk of going to jail?” Dr. DeShawn Taylor, the clinic’s owner, said.

The team at Desert Star allowed us into their clinic last Friday, for what they feared would be the final day of abortions as they awaited word on a court case that could have, and still may, end abortions in Arizona completely. The clinic didn’t schedule appointments beyond that day, in case the judge ruled from the bench.

The staff squeezed in patients seeking abortions and didn’t allow walk-in appointments that day. The receptionist told people who called in that day that they couldn’t schedule abortions for next week.

Patients’ ability to get care was up in the air, like it has been multiple times in the past two months.

The clinic’s staff anxiously waited to hear whether a judge in Pima County would lift an injunction on a 1973 case that prevents Arizona from enforcing an outright ban on abortion, a case that all sides agree will decide the fate of abortion access in Arizona going forward.

The Pima County judge didn’t rule last Friday. Instead, the judge said it’ll be a few more weeks before they make the decision. That gave abortion providers a few more weeks, at least, to operate legally. Abortions can continue, under all the old pre-Dobbs rules. That’s more certainty than abortion providers have had since the Dobbs ruling.

“I’m glad to have another month,” Taylor said.

It seems clear, though, that abortion will become much more restricted in Arizona in the near future — whether through a pre-statehood outright ban on the procedure or a 15-week ban that’s set to go into effect on Sept. 24.

Meanwhile, the political work to solidify more access to abortion has already begun, with abortion backers looking toward a 2024 ballot measure to protect the right to abortion in some fashion, as polling has consistently shown Arizonans want. Democrats are working to make abortion access a centerpiece of the 2022 midterm elections, hoping that a Democratic governor, combined with the courts, can stave off efforts to further restrict abortions.

Until then, abortion providers will struggle to keep their doors open in states like Arizona. Already, more than 40 clinics in 11 states across the country closed their doors in the month after the Dobbs ruling, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Providers fear that even if reproductive rights proponents are successful in the long run at getting some level of abortion legalized here, as they were in Kansas last month, it’ll take years to rebuild access because abortion providers will have closed. They’re already struggling to recruit staff to do this work, and training for new providers is hard to come by.

The Dobbs ruling may not mean the end of abortions in Arizona, but it’s taking its toll on the abortion industry.

Clinic adapts after Dobbs ruling

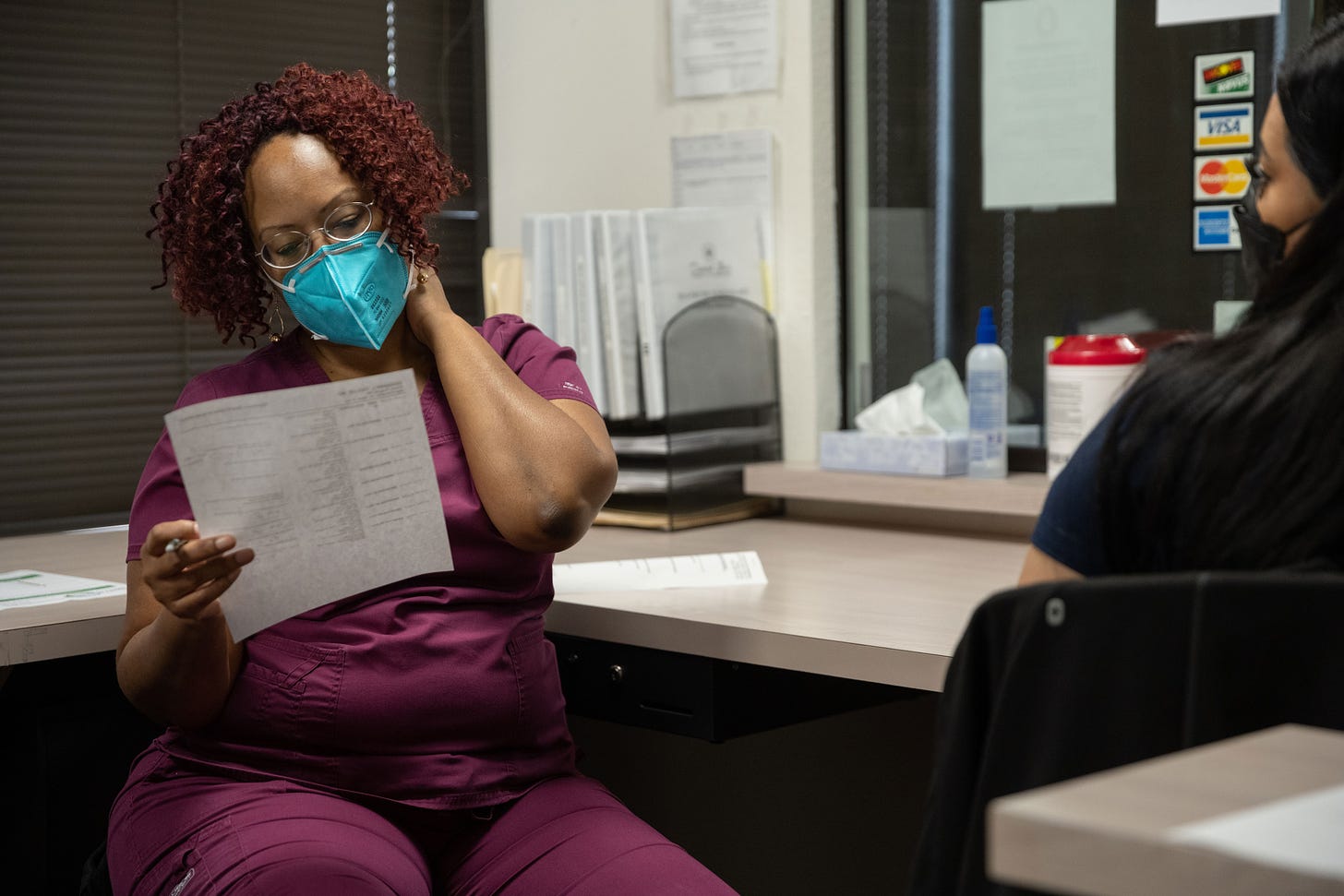

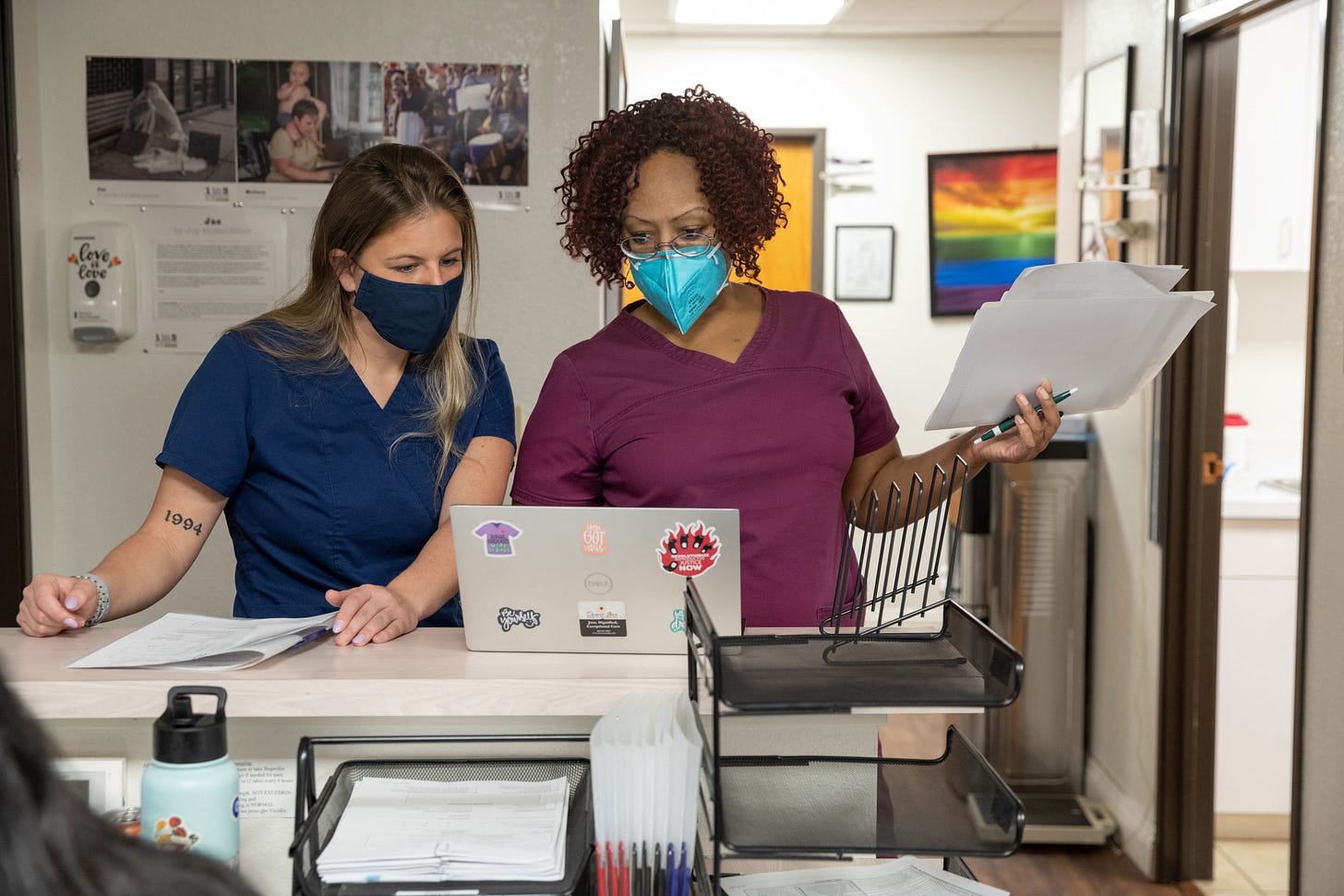

At 9 a.m. on Aug. 19, Desert Star’s four employees huddled to go over the day’s schedule.

The clinic had six abortions scheduled. Most were around the 6-7 week range of early pregnancy.

Because of the legal uncertainty, Taylor’s clinic did just five abortions in all of July. She hasn’t been able to resume surgical abortions, her specialty, because of staffing problems, meaning she is only providing medical abortions by pill, up to 11 weeks of pregnancy.

“I am a complex family planning-trained abortion provider who can provide abortion care later in pregnancy,” Taylor said. “And to not be able to offer that to people because I have staff who are scared to do it, was really, really harming me emotionally.”

She’s tried to recruit a nurse who can help with surgical abortions, but hasn’t been able to find someone yet. She got on a Zoom call with someone who recruited nurses who was going to help her, but that was a month ago. There’s been no follow-up. Some people she hires don’t show up, or stop coming to work after only a short stint. The attrition and uncertainty affects the clinic’s ability to provide care, and the last few months hasn’t boosted her faith in the public’s ability to turn outrage over Dobbs into action.

“There's a lot of outrage and righteous indignation and people wanna march and rally, but I don't know that it's necessarily going to translate to people going to the polls,” she said. “Because there were so many people who wanted to help in this clinic, to help people get abortions, but that didn't translate to actually showing up in the clinic to help people get abortions.”

She’s worried about the long term financial picture for the clinic. She takes donations and has gotten some grants to help cover bills this summer. She’s always provided non-abortion care, too, including annual exams, STD testing, miscarriage management and gender-affirming care.

But abortions are a key part of her clinic’s work and its revenue stream.

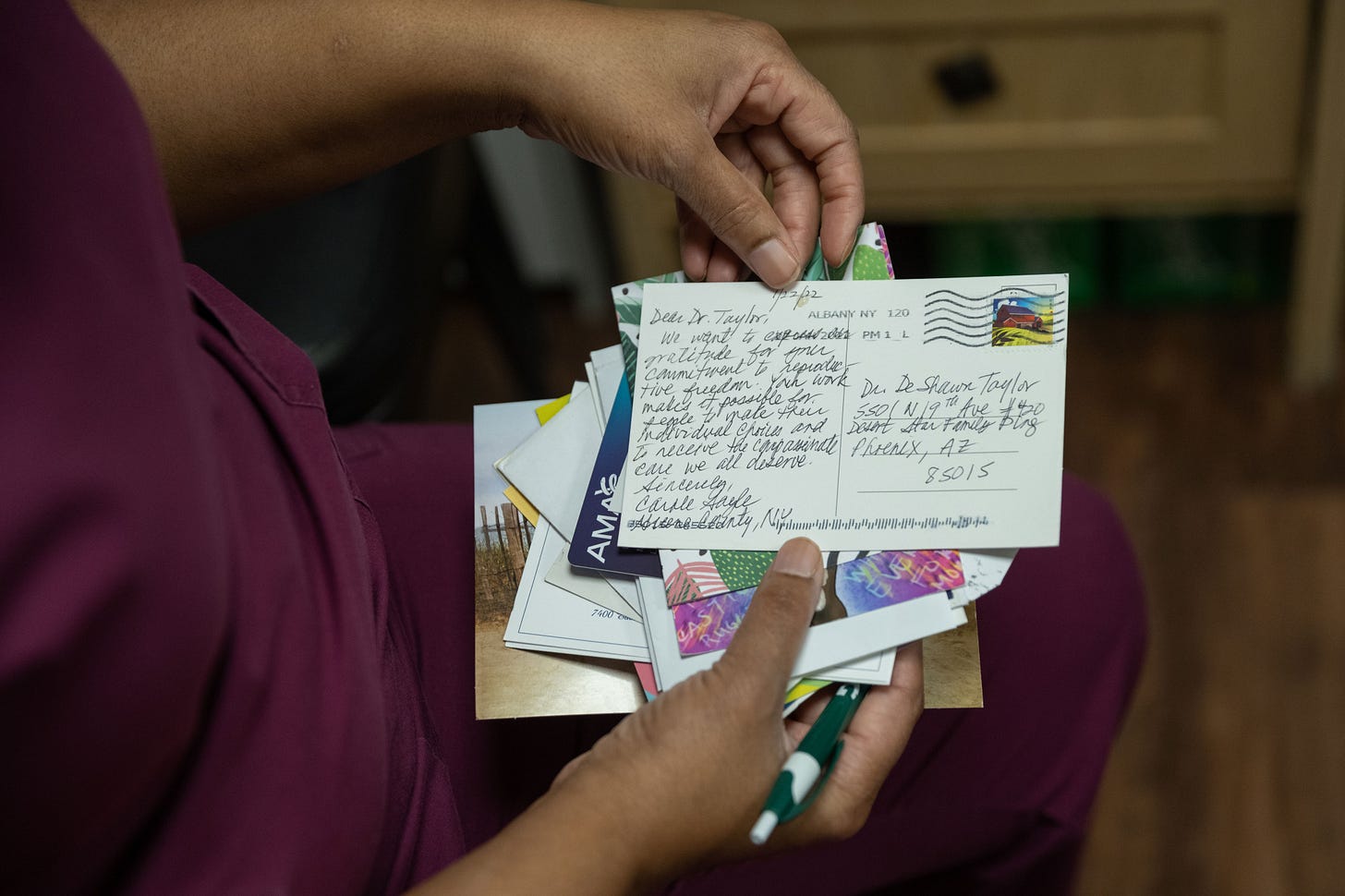

And she knows the patients need her. Taylor shared the thank you cards she’s received over the years, some gathered in a scrapbook, a testament to the care she’s offered to Arizonans for more than a decade.

Legal landscape leads to confusion

In the aftermath of the Dobbs ruling, Arizona politicians failed to clarify and actively spread false information about the fate of abortion here, putting abortion providers in limbo through the state’s inaction.

Several conflicting and overlapping laws could apply.

Arizona has a pre-statehood outright ban on the books, which was prevented from being enforced as part of a 1973 court case, and a newer 15-week ban that’s not yet in effect. A fetal personhood law added to the confusion because it granted rights to fetuses the same as those available to all people, though that law has since been blocked by the courts.

The 15-week ban, set to go into effect on Sept. 24, would provide at least some access to abortion, but far more limited than the Roe standard required nationwide, which allowed for abortions up to the point of fetal viability, usually around 22 to 24 weeks.

Attorney General Mark Brnovich and advocates for abortion both pointed to the 1973 case, saying an injunction needed to be lifted in order for the pre-statehood ban to be enforced. Brnovich filed to get it lifted, and the judge should rule next month.

After Dobbs, Arizona Senate Republicans put out press releases saying abortion was now illegal, though that was not true.

The confusing legal landscape and scary headlines have trickled down to patients, too.

For the few abortion providers still offering care, operations look different than they used to. At Camelback Family Planning, people line up to wait starting in the early morning to try to get an appointment, as detailed in the Los Angeles Times earlier this month.

At Taylor’s clinic, they’ve done walk-in appointments and tried to follow up with abortions quickly because the law could change.

For each procedure, her staff gathers the abortion pills — mifepristone and misoprostol — and other medications that help during and after the procedure, like pain medication, anti-nausea medication and a single dose of an antibiotic. The clinic, in normal times, provided both surgical and medical abortions, but they don’t have the staff to help with surgical abortions now.

Taylor has to attest that she’s not breaking several state laws: She has to sign off that the abortion isn’t being done because of the race or sex of the fetus, or because the fetus has a genetic abnormality. She has to attest that she did not witness a fetus born alive, an impossibility for an early-stage pregnancy.

With the patient, she goes over detailed instructions about what will happen next, preparing them for all the possible side effects and knowing when to call her for further help.

A 19-year-old Phoenix woman came in that morning. She would have preferred a surgical abortion, but decided to get a medical one at Desert Star because she felt comfortable and not judged when she got a surgical abortion here about two years ago. Surgical abortions can be completed more quickly in a medical office, while medical abortions can take a couple days at home.

“They were telling me that they were only offering medical, so I went through with that, because other places were literally like, ‘Not at all. No surgical, no medical,’” she said.

She found out she was pregnant a week before. She worried she wouldn’t be able to find a provider to get an abortion. She wasn’t ready to have a kid. She was confused about whether or where she’d be able to get care, or if abortions were legal in Arizona anymore.

“I was even freaking out,” she said. “I was like, oh my god I'm gonna have to go to California. I was literally thinking all the worst at first, but then I was like no, I'm gonna call this place first, Desert Star, and see what's going on and what they think.”

They scheduled her for a consultation, then the abortion. She said it all went smoothly and she felt taken care of. And she knew the broader abortion landscape had to be affecting Taylor and the staff, yet they all made an effort to help her.

People who need an abortion should know they’re not alone, that they still have options, even now, she said.

Taylor never thought she’d run an independent abortion clinic. She wanted to be an academic physician who specialized in abortion, likely as a department chair at a university. But she realized people didn’t want to do abortions, and the number of providers had dwindled. She knew where she was needed.

“It makes sense because I remember back in the day, I was the protector of the girls, fighting on the playground for the girls. That was me in elementary school. It's definitely a calling,” Taylor said.

Now, she also runs a nonprofit that helps other providers learn to give surgical abortions. In prior years, she’s had visiting medical professionals from all around the country and parts of Canada shadow her, learning from her, most weeks out of the year.

The weeks that the clinic was closed this summer and the legal uncertainty affected her ability to train new providers, too. She’s trying to find ways to keep training — even if it’s out of state.

She’s been talking with a provider in New Mexico, where she might be able to fly in and provide first trimester surgical abortion services. It would add to that clinic’s services and allow her to continue training future abortion providers.

“I'm thinking outside of the box here to try to make sure that there are abortion providers for the future,” Taylor said.

What it’s been like since June

The clinic, like all abortion providers in Arizona, is in a moment of major flux. The staff has tried to help as much as possible for as long as possible, but it’s a constant, daily challenge.

Rose Espericueta, the clinic’s receptionist, wears a pink “mind your own uterus” pin. Above her computer, a sign shows a review from a patient who complimented the clinic’s safe and comfortable atmosphere. The windows of the waiting room are blocked out. To get into the fourth-floor office, people need to ring a doorbell, and Espericueta will let them in.

She answered the phones in late June on the day the Dobbs decision came down. She had to break the news to people that they couldn’t keep their appointment. They’d have to go online and try to find somewhere else to go, but there were very few options in Arizona at that time.

Some cried. Some yelled. Some were shocked. Frustration came through. She had to call upcoming surgical appointments and tell them they were canceled. They could come get their medical records if they needed them.

“You don't get into this business, you don't get into this health care, to be telling them no,” she said. “You’re trying to help them. And it sucks because I honestly told everyone no that day.”

In the weeks since the fetal personhood law was blocked, after which Desert Star resumed abortions, the phone lines have started ringing right away at 10 a.m., and appointments have filled within minutes, Espericueta said.

Sometimes, callers will lay out their reasons for needing an abortion, venting and explaining what’s going on in their lives. She stops them: They don’t need to provide her a reason. The fact they want one is reason enough. They don’t need to validate or explain themselves.

Last Friday, when people called to try to schedule abortion consultations or appointments for next week, Espericueta again had to tell them that she couldn’t put anything on the books for next week. It could be the last day today, she told them. There’s a court hearing.

“It’s just a waiting game for us,” she said.

The waiting game ended — temporarily — that afternoon.

In the Pima County court case, the attorney general’s office said the court should lift the injunction and allow the ban to be enforced, noting that while the law itself is very old, it’s been reaffirmed by the Legislature since then. Planned Parenthood of Arizona argued that the state needs to harmonize the myriad, conflicting laws on the books that allow some level of abortion access.

For now, legal abortion access has another month. Because of a procedural issue, Pima County Superior Court Judge Kellie Johnson said she won’t rule until on or after Sept. 19.

Taylor tells her staff that abortion is still legal, and they have another month to carry on the same way they have been: Fitting as many people in as they can, up until they’re forced to stop. A round of relief, of “oh thank gods,” spreads through her small team.

No matter what ultimately happens in the case, Taylor doesn’t plan to leave Arizona to provide abortions in another state. She’s put down roots in the 13 years she’s been here.

Her time providing abortions in her Arizona clinic is limited. Just how limited isn’t yet clear.

“I had to work through, mentally and emotionally, that eventually I'll do abortions again here, but I have to make peace with not doing abortions here for however long, until we can swing the pendulum back and get it back,” she said. “Because otherwise, I wouldn't be able to function.”

Thank you for supporting independent local journalism in Arizona. For this piece, we tapped Caitlin O’Hara, a member of the Juntos Photo Coop who lives and works in the Sonoran desert, to make photographs that help tell the story. To subscribe to the Arizona Agenda and pay to support our work, click the button below.

Thank you for covering this important issue.

Thank you Rachel, another great article. I always love the attention you pay to the individuals in your stories. I have been enjoying your articles since your Capitol Times days.